Featured Photo: Caleb Jones

The story of Muir Woods may seem like ancient history, but there's always more to learn when it comes to this precious Marin County treasure.

Indisputably a crown jewel of Marin County’s natural splendor, Muir Woods remains a popular destination for tourists and locals alike. From walking among old growth coast redwoods to catching a glimpse of a northern spotted owl or a river otter, the lush surroundings and breathtaking scenery of Muir Woods has long been touted as a success story of conservation and a testament to the importance of our national park system.

History

Named in honor of conservationist John Muir, Muir Woods holds the distinction of being the tenth national monument to be designated under the Antiquities Act of 1906 as well as the first to be in proximity to a major city and the first to consist of formerly privately-owned lands. In this case, the owner was one William Kent, who purchased 611 acres of land — including the site of the future Muir Woods — from the Tamalpais Land and Water Company in 1905 for $45,000.

In 1907, Kent would go on to donate 295 acres of land as a means of circumventing an eminent domain dispute with a Sausalito water company intent on damming Redwood Creek. By 1908, President Theodore Roosevelt had declared the land a national monument, establishing the geography of Muir Woods as we know it today.

Recently, however, a new collaboration between Muir Woods staff members and the Golden Gate National Recreation Area (GGNRA) interpretative team has shed new light on the park’s long, complex history in an effort to rectify omitted, vital context from the narrative.

History (Updated)

For the next six months, visitors to Muir Woods who visit the park’s “Path to Preservation” information placard will find the structure “updated” with caution tape, a slew of sticky notes affixed to a given timeline of Muir Woods’ history, and a letter explaining the intent behind the changes.

The idea, in essence, is to supplement the long-publicized history of how Muir Woods came to be — a process previously credited almost exclusively to “influential, philanthropic white men” — with information on the indigenous peoples and women who also played vital roles.

While the placard’s official timeline begins with the establishment of the first national park on the planet, Yellowstone National Park, in 1872, newly affixed sticky notes remind readers that Muir Woods’ own story begins back in the time of Coast Miwok and Southern Pomo people.

“20,000 Coast Miwok and Southern Pomo people (at 850 sites) tend, manage and/or initiate prescribed burns to what is now Marin County and southern Sonoma County,” one reads. “Their practices take care of the land and themselves.”

In line with the park service's mission to #TellAllAmericansStories, Muir Woods rangers past and present have been working together to tell a more full history of the founding of Muir Woods. Learn more through this SF Gate article: https://t.co/wDDuUu8G7H #MuseumsAreNotNeutral pic.twitter.com/odBlSofEiu

— Muir Woods NPS (@MuirWoodsNPS) September 2, 2021

Beyond the Timeline

Other notes directly below this initial addendum include information about Spanish missionaries beginning to use the labor of Bay Area indigenous peoples starting in 1769 (which in turn disrupted the latter’s ability to serve as a steward of the land), the 1861 act of Congress that extinguished Indian title to almost all land in California (including Muir Woods), and one dated to 1869 in reference to namesake John Muir’s record of racism towards Indigenous people in his writings (later published in 1911).

A common theme of conservation-minded white men who helped ensure protection for America’s natural wonders, but were also well-documented racists, is also charted in the course of these notes. One adds an addendum to a spot on the timeline dedicated to Gifford Pinchot, who in 1898 was appointed chief of what is now the U.S. Forest Service and advocated for “scientific forestry” according to the original placard.

“…and eugenics,” adds a sticky note directly beneath this blurb before providing a Merriam-Webster definition of the term. “Pinchot is among several prominent eugenicists that project racial superiority onto redwood trees and are especially active in their preservation.”

The minimized role of women in our national park story is another focus of this project, be it their championship of establishing Big Basin State Park as California’s first state park and preserved redwoods in 1902 or the fact that it was a women’s club (the California Club) who were the first to campaign to save the land that we today know as Muir Woods.

Serving as an important reminder that history is far more complex than what fits on a placard, this temporary installation is a noble effort to set the record straight and yet another reason to plan a visit to one of Mt. Tamalpais’ most iconic treasures.

Happy National Owl Day! Spotted owls are very important to the health of the redwood ecosystem. We monitor the population of the threatened northern spotted owl at Muir Woods. To learn more click here: https://t.co/FkPv3TIT5p pic.twitter.com/W3iIumS959

— Muir Woods NPS (@MuirWoodsNPS) August 4, 2021

Visitor Guide

What to See at Muir Woods

According to the National Park Service, in 2018 alone, Muir Woods National Monument welcomed nearly a million visitors. What is it about Muir Woods that attracts so many people? For starters, the 558-acre monument is home to one of the last remaining ancient redwood forests in the entire Bay Area, including redwoods that are nearly 1,000 years old and some that are taller than 250 feet.

In addition to the stunning canopy of trees, Muir Woods also plays host to more than 380 different plants and animals. Though the redwoods unquestionably dominate the scene, visitors may also encounter California bay laurels, bigleaf maples, and tanoak trees.

When it comes to animals, take your pick from over 50 species of birds, including the northern spotted owl and pileated woodpecker, and a bevy of different mammals ranging from shrew moles to bats to sea otters. Redwood Creek in Muir Woods is also a critical habitat for Coho and Steelhead salmon, who can usually be spotted spawning between December and January (Coho) and January and March (Steelhead).

Those interested in stretching their legs can choose from six miles of trails contained in Muir Woods, including a 30-minute loop, an hour-long loop, and a 90-minute loop — each offering views of the park’s famed old-growth coast redwoods.

If you’re looking for a simple place to start, try the Muir Woods Visitor Center or the Muir Woods Trading Company and Cafe. Both are open every day and offer a ton of fun, informative options for how to make the most of your visit.

How to Get There

Though Muir Woods is technically open 356 days a year from 8 a.m. to 6 p.m. daily, you’ll want to do a little advanced planning before paying the park a visit. That’s because, starting in 2018, Muir Woods introduced a parking reservation system to drastically limit the number of cars permitted entry each day.

In light of these new procedures, visitors can either reserve a parking spot in advance by visiting GoMuirWoods.com or, if you’re planning to see the park on a weekend or holiday, by catching a shuttle at Pohono Park & Ride (100 Shoreline Hwy, Mill Valley, CA 94941). Free parking is available for shuttle riders, though be aware that the park charges $15 per adult for entry.

As a final note, there is no cell phone service or WiFi within or around Muir Woods National Monument, so visitors are advised to download parking reservations in advance.

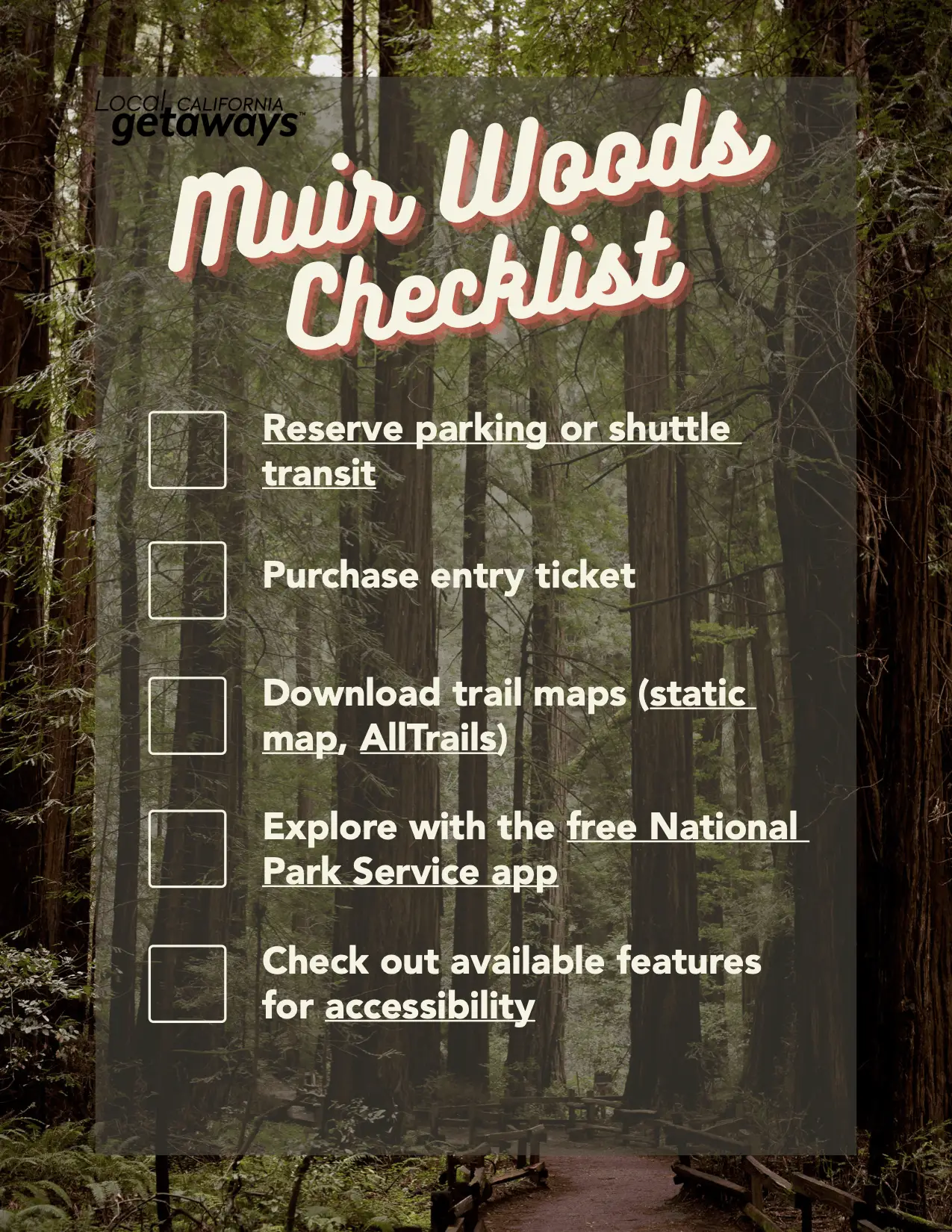

Checklist

Click to open PDF with links:

Want more travel inspiration and tips from locals?

Follow us on Instagram @localgetaways!